The Path to Become a Wine Expert

To become a wine expert, you need first to master the analytical methods of wine tasting then forget all about them, according to researchers Latour and Deighton (1) who published their findings in an open source publication. Of course this provocative statement captured my attention and I read this paper. Here are my key take-aways.

This publication is not an easy read at first, however the authors structured the paper in such a way to provide the context of their work, their 3 research hypotheses, and their actual contributions, which are nicely summarized after each section.

What do we know about wine expert abilities?

Wine experts as many other experts have been the subject of many studies, which have mainly focused at comparing their abilities to those of novices.

This previous literature showed that experts:

- are very fluent in relating language to perceptions, whereas novices lacked those skills;

- demonstrate better ability to recognize wine attributes and to differentiate wine styles;

- use a prototypical approach to wine tasting, almost a logical approach that would identify some features enabling them to deduct other wine attributes.

This approach can be tricked as Morrot et al. (2) did when they added red colorant to white wines and experts described these wines with typical red wine aromas.

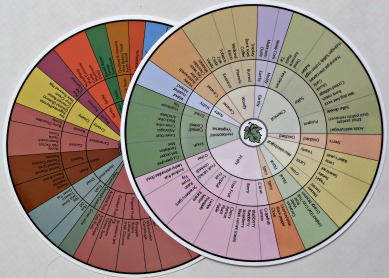

It was also showed that novices can be taught to become more fluent in matching their perceptions with words using rule based grids or lexicon such as the wine aroma wheel created by Dr. Ann Noble.

What about the apprentice-wine experts, the wine enthusiasts?

In this paper, the authors acknowledge an intermediate stage to the path of expertise which is being a wine enthusiast, a person who has an interest in wine and has taken some sort of wine education course. No literature bothered to study how a wine enthusiast can become a wine expert.

So they tested 3 hypotheses and I quote:

- Novices (enthusiasts) will demonstrate better memory performance when encoding hedonic experiences analytically (holistically).

...meaning that novices and enthusiasts will memorize better the wine characteristics when they learn analytically for novices or holistically for the enthusiasts. - A learning approach that encourages the enthusiast to encode their experience into a narrative structure will result in better memory performance than one that encourages a decompositional structure.

...meaning that the use of narrative to learn and memorize works best. - A learning approach where the enthusiast encodes the taste experience using images rather than words will lead to greater memory performance.

...meaning that the use of images, drawings to learn and memorize works best.

How do wine experts think they learned?

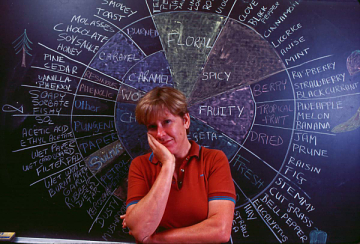

In the first part of their investigation, the authors conducted semi-structured interviews with Master Sommeliers, a status ranking high on the scale of wine expertise. They asked sommeliers how they developed their wine tasting skills to reach that upper level of expertise. What they shared was so revealing.

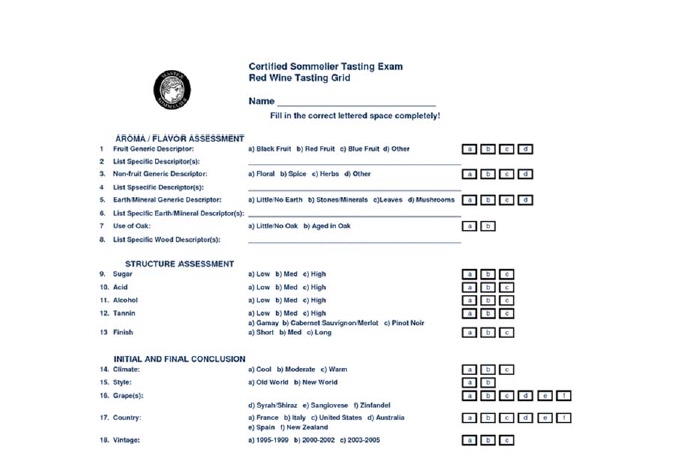

They reckon that as beginners, you need a framework to learn. A grid to report your tasting notes such as the Wine and Spirit Education Trust (WSET) grid as shown below, the Wine Aroma Wheel to help you decompose your aroma perceptions. As you practice, you start looking for clues and want to be “right”.

“Jason […] discussed the analytic approach of wine as a logical problem: “So if it’s X, Y, Z, P, D, Q, therefore it must be T. So you have to be able to – you have to be able to make that statement and defend it.”

In my opinion, this is where expertise can lead to tasting with your head rather than your senses. Looking for cues to have “the right answer” may tempt you to let go of the use of your senses to experience the wine. It is true that the tasks of wine experts are often to judge wine quality, check for off-notes, identify a wine style, grape varietals etc. In a way there are true answers and this attitude can affect the objectivity of the wine taster.

Yang: “I can tell you that I remember first getting into it; it was all about, oh, memorizing the boxes and just hitting the grid, hitting the grid– as opposed –letting the wine speak for itself, I was speaking for the wine, almost like making up descriptors, just ’cause I thought I was filling in the boxes.”

Fortunately, at some point in their career, these professional sommeliers experienced an ah! ah! moment, when they realized that all their analytical and flowery language was not helping their customers. Several interviewees shared that they slowly “get off the tasting grid” and use visualization to talk about the wine. The authors were particularly inspired by a sommelier named Ronald, who uses shapes to represent what he tastes, and that’s how he teaches wine appreciation as well.

So the authors designed several experiments to test if visualization could help wine enthusiasts to transition towards wine expertise. Note that their research involved wine, coffee, chocolate, and beer.

Two strategies that may help you become a wine expert

The authors define a wine enthusiast as a person who has “interest and experience with the target product, a minimum of five years tasting and some educational involvement.”

The task of the respondents were similar in the different experiments: they had to taste one wine sample, perform the learning task, and then come back and identify the wine they learned about among a set of 4 similar wines. The learning task was found effective if the respondents identified the correct wine. Other questions were also asked to gain more information on the effects of the learning tasks.

Experiment 1: Testing impact of analytical tasting versus using a narrative to describe and memorize your perceptions

Researchers found that drawing one’s perceptions when wine tasting increased respondents’ performance at identifying the correct wine sample in the 4 wine exercise. Writing a narrative, a story on the wine, improved performance of wine recognition over a classical analytical wine tasting using a tasting grid.

This is very interesting as it showed that drawing enhanced enthusiast tasters’ ability to memorize the wine characteristics.

While these holistic learning methods increased enthusiast tasters performance, the writing or the drawing remains personal to the taster and may not be understood by other people who may wonder how the wine tastes like.

Experiment 2: Holistic tasting as a method to memorize your wine perceptions

In the second experiment, the authors wanted to determine if the holistic method of tasting could transport the enthusiast taster into a taste experience that would facilitate a better memorization of the event; as the master sommeliers described earlier. Although the study didn’t include wine (only chocolate and beer) the learnings may be extrapolated to wine.

The participants attended a class to learn about the product and how it was made. Then they tasted one product (an IPA beer or artisanal cranberry-dark chocolate) and were asked to write or draw their experience. After that, they filled out a questionnaire asking how emotionally involved they were while writing and drawing. Researchers found that those enthusiasts who were highly involved emotionally had a better chance to identify the target product in a set of four and that drawing led to superior performance.

So what?

These results suggest that drawing might be a good strategy for an individual to learn about wine, especially wine varietals or wine regions so that he/she could identify them correctly in their professional activities. Using these narratives to communicate one's wine experience to other people (customers or friends) may not work, although this could be an easy experiment to set up.

Did the authors validate their hypothesis? YES!

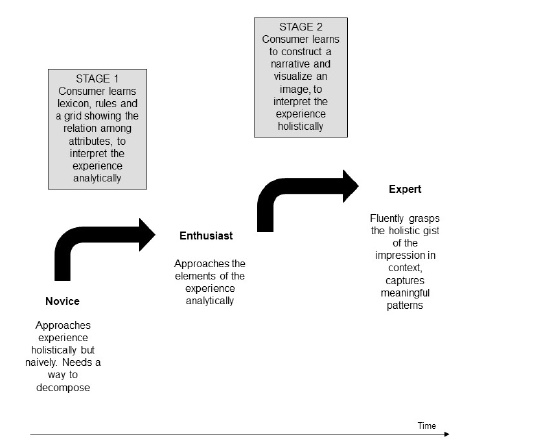

And they summarize the staged process they identify as a possible path to become a wine expert in the figure below.

Going back to their 3 hypotheses, their experiments concluded that YES:

- Novices (enthusiasts) demonstrate better memory performance when encoding hedonic experiences analytically (holistically).

- A learning approach that encourages the enthusiast to encode their experience into a narrative structure results in better memory performance than one that encourages a decompositional structure.

- A learning approach where the enthusiast encodes the taste experience using images rather than words will lead to greater memory performance.

If you are reading this article, you are either beginning your wine journey, are an enthusiast, or a wine expert.

Experiment at your next wine tasting to draw what you perceive

about the wine.

References

Note: the illustration and quotes are excerpts of the original article

Latour, K., & Deighton, J. (2018). Learning to become a taste expert. Harvard Business School Research Paper Series #18-107.[Electronic version]. Retrieved [08-19-2018], from Cornell University, School of Hotel Administration site.

Morrot G., Brochet F. & Dubourdieu D. (2001). The Color of Odors, Brain and Language, 79, Issue 2, 309-320.