Do Expensive Wines Taste Better?

What attributes can justify the price of expensive wines? Is this saying ‘The more expensive the bottle, the better the wine quality’ true?

It is true indeed that high end wines can be more expensive to produce: tendering a single block vineyard, hand harvesting, or using French oak barrels has a superior cost. However, does this cost make them more palatable?

It is also true that some wine regions have developed such a reputation or image that their product prices can be artificially boosted. They become collectors items for which there is no price limit.

Do most expensive wines really taste better? Or is it a matter of perception?

Perceived quality of expensive wines is a matter of context

When a novice wine taster begins her journey shopping for wine, she is usually confused by the amount of information that she has to consider before making a decision: red/white/rosé/sparkling, country of origin, grape variety, vintage, expert reviews, awards etc.. Facing that wine shelf can make her feels dizzy and the only way to escape is to use a cue that she is familiar with: price! Can she expect to have a better sensory experience if she paid $35 instead of $25 for a bottle of cabernet sauvignon?

Wine quality is the result of your sensory perceptions in the context of what you know about the wine and of where you are when tasting this wine. When you taste blind, nothing can alter your judgement and you can have a true response on whether you like this wine or not. As soon as you have a glimpse of that bottle, you hear comments on the wine, your sensory experience and appreciation can change. And serious research has demonstrated that effect.

What do research studies show about expensive wines?

The first sensory lab

Every year, the wine sensory class at Brock University starts with this experience where the students are invited to taste three wines in three different rooms.

- The first wine is a VQA bordeaux blend from the Niagara Peninsula;

- the second wine is a trendy brand in a TetraPak;

- the third wine is a first growth from St Emilion, in Bordeaux.

The students start their experimental journey in the wine cellar: try to picture it! The lights are dimmed, candles are lit and glasses from each wine await them on barrels used as tables. Classical music plays in the background.

The instructor welcomes them to their first sensory class and invites them to sample the wines while she gives an overview of the sensory journey they are undertaking that day. Students chat, mingle, are impressed; they take some notes on the wines; it’s a class nonetheless.

Then they move to the sensory lab where wines are presented in coded glasses, and they are asked to rate certain attributes comparing these wines. They all sit in individual booths under red lights. Aromas are more intense.

Finally, they arrive in the fermentation lab where they gather around large tables where some snacks are served and again they have to answer another set of questions on these wines. One of the disclosed goals was to test the effect of environment on the taste of the three wines. All the students comment that indeed, these wines tasted different in the sensory lab. Some of them had a memorable experience tasting a first growth. TetraPak wine is ok, can be handy for a picnic.

Then comes the big reveal. The same VQA wine was poured and presented in these different “containers”. Not only the environment altered the taste but also the perception of drinking wines with likely different qualities.

The more expensive wine tasted better because it was expected to taste better; the cheap wine was less appreciated overall because wines in boxes cannot taste as good as a first growth.

Learning from experimental psychology

My colleague Christine Lange conducted several experiments during her doctoral research to clarify the concept of perceived quality by consumers.

Two were on wines and both had the same design.

Wine consumers were invited to participate in a tasting based in a sensory lab.

The first task was to taste a series of wine samples presented blind and then to rate their overall liking on a hedonic scale (from I don’t like it to I like it very much).

Second task consisted in evaluating wine labels and based on the information presented, consumers had to rate how much they thought they would like the wine under these labels (i.e. what were their expectations?)

Third task was to taste each wine along with its label and to rate their overall liking again. All samples were presented in different orders among participants, hence using good sensory practices.

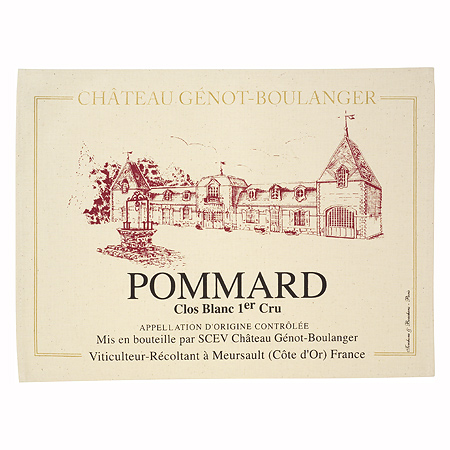

Findings showed that the premium wine appellation was expected to be liked better but on a blind taste, it was generally not preferred to the generic label.

This was true for Champagne wines and Burgundy wines.

When the wines were presented with their labels, consumers tended to rate higher the premium appellations although initially their liking rated blind was lower.

The psychologists called this phenomenon "cognitive dissonance". Realizing that their evaluation may be "wrong", consumers corrected their initial perceptions due to the information showing that their appreciation should be conform to their expectations. Again, expensive wines should taste better.

Learning from experimental economics

Goldstein et al (2008) look at correlation between price and overall liking. More than 500 participants tasted wines priced from $1.50 to $150 a bottle. Tastings were conducted in a double blind manner meaning that both wine servers and the tasters were unaware of the nature or price of the wines.

Findings showed that “the correlation between price and overall rating is small and negative, suggesting that individuals on average enjoy more expensive wines slightly less. For individuals with wine training, however, we find indications of a positive relationship between price and enjoyment.” Again expensive wines do not taste better.

Almenberg and Dreber (2009) designed an experiment to study the effect of price knowledge on wine appreciation. Their findings showed that “Disclosing the high price before tasting the wine produces considerably higher ratings, although only from women. Disclosing the low price, by contrast, does not result in lower ratings.” So higher prices created higher expectations of quality for women who in turn gave higher ratings.

So do expensive wines taste better?

The answer lies in your own expectation!

Home >